Authors: Jessica McCann & Tonantzin Juarez

July is National Minority Mental Health Awareness Month, also referred to as Bebe Moore Campbell National Minority Mental Health Awareness Month or National BIPOC Mental Health Awareness Month. To commemorate this important topic, we focus this month’s Policy blog on the mental health issues unique to Indigenous populations in the United States (U.S.). Centuries of colonialism, genocide, racism and marginalization have led to mental health disparities despite generations of Indigenous practices facilitating positive mental health. We examine these mental health issues, promising programs, and a return to Indigenous values and their integration within our modern healthcare system.

Indigenous Knowledge

It is important to note that Indigenous populations span the globe and, even within the Americas, are extremely diverse in language, background, cultural practices, and religious traditions. For centuries, Indigenous practices fostered positive mental and physical health with intergenerational holistic healing, traditional plants and herbal medicines, and healthy Indigenous food systems, as outlined in the Indigenous Determinants of Health Report. Aspects of Indigenous life, including spirituality, ceremony, strong connections with elders, enduring attachments to Indigenous lands, and other practices strengthened mental health and emotional well-being while protecting Native lands and resources. However, many of these practices were systematically erased by the “discovery” and colonization of the Americas, beginning in the late 1400s and first codified by the Indian Removal Act of 1830.

Colonialism, Forced Assimilation and Health Disparities

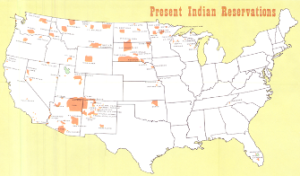

As illustrated by Dr. Donald Warne in “Representation Matters: Indigenous Peoples in the Health Sciences,” his 2024 Weitzman Institute Symposium keynote address, post-colonial Indigenous lands, once covering the now-United States, have been reduced to the reservations shown on the map shown below:

Map by Sam B. Hilliard and Dan Irwin

This systematic relocation and genocide of Indigenous populations in North America led to the loss of sacred traditions, lands, and cultural practices. Government-sponsored forced assimilation programs in the U.S. and Canada, including the removal of Indigenous children from their homes and placing them in often-abusive boarding schools or with non-Native families, further removed Indigenous populations from traditions that facilitate positive mental and physical health. Additionally, these forced assimilations destroyed families and caused generational trauma still felt in 2024.

Forced assimilation, loss of lands, generational poverty and trauma, health care and behavioral health services access barriers, lack of healthy food, lack of representation in the healthcare workforce, discrimination and bias, limited educational and occupational opportunities, and even climate change have led to countless, well-documented health disparities among Indigenous populations in the U.S. Specific to mental health, recent research shows that non-Hispanic Indigenous populations have the highest suicide rates of any racial or ethnic group in the U.S., which contributes to shorter life spans and sustained generational trauma. Overdose rates among the U.S. Census Bureau-designated group “American Indian and Alaska Native” have increased faster than in any other racial or ethnic group and Indigenous populations suffer from post traumatic stress disorder at higher rates than non-Indigenous populations. Despite these data, rurality, isolation, an underfunded Indian Health Service, and workforce shortages contribute to a lack of viable behavioral health care options for Indigenous populations.

Indigenous Programs Leading the Way

Yet, Tribal organizations and Indigenous leaders are making progress in narrowing mental health disparities. We outline just a few of these strategies and programs below.

Expanding Access to Medical School

It is well established that when a healthcare workforce resembles the patient population, health outcomes improve. Yet, according to a 2018 AMA Council on Medical Education report, the physician workforce only includes 3,400 American Indian and Alaska Native physicians, representing 0.4% of the physician workforce. Additionally, only 9% of medical schools have more than four American Indian and Alaska Native students, while 43% have none.

More medical schools must replicate the successful University of North Dakota initiative Indians to Medicine (INMED) to diversify the workforce and increase American Indian and Alaska Native representation. Since its inception in 1973, INMED has become a successful Indigenous medical training program, graduating 281 American Indian and Alaska Native medical trainees as of 2024. Universities can also partner with Tribal nations to widen medical school pathways for American Indian and Alaska Native populations. For example, the Oklahoma State University College of Osteopathic Medicine at Cherokee Nation is the first Tribally-affiliated medical school in the U.S., with 20% of the inaugural class identifying as Native and 35% of students continuing their training in a rural or Tribal residency program. This program is also unique in its approach as it incorporates Indigenous traditional medicine into its curriculum and requires students to train at various Tribal facilities.

Ohkomi Forensics: Addressing the Missing and Murdered Indigenous People (MMIP) Epidemic

Native Americans make up 6.2% of Montana’s population yet account for 30.6% of missing persons, and homicide is the third leading cause of death for Native women. Ohkomi Forensics, a Native-led lab, is dedicated to addressing the aptly-labeled Missing and Murdered Indigenous People (MMIP) epidemic, especially as many cases go unsolved by non-Indigenous law enforcement. Ohkomi Forensics brings advocacy, fieldwork expertise, and “reservation life” experience to forensics, offering closure and justice to families grappling with cold cases. The lab’s unique approach, embedding cultural sensitivity, reshaping anthropological methods, and leveraging intentional collection and use of data, make it a model for other Native-led organizations dealing with mental health, community violence, and trauma.

Traditional Healing to Treat Addiction

As previously mentioned, the overdose crisis has disproportionately impacted Native communities. Tribal communities are using opioid settlement funds to design and implement recovery programs based on traditional healing methods. For example, the Mi’kmaq Nation spent $50,000 of its settlement funds to build a healing lodge. The Nation uses the lodge for traditional sweat ceremonies requested by Tribal members to complement counseling and other addiction treatments. Participants say that emerging from the lodge is like being cleansed and reborn. Other settlement-funded traditional practices include smudging ceremonies, basketmaking, and Tribal language lessons, all of which can contribute to improved mental health.

Supporting Caregivers via the Family Spirit Program

The Family Spirit Program is an evidence-based and culturally tailored home visiting intervention, developed by Tribal populations and delivered by Tribal community health educators. These educators deliver care to pregnant mothers and children from birth to age three, with the goal of improving maternal and child health, leading to positive child rearing, school success and better behavioral health outcomes. Currently over 100 Tribal communities across 26 states implement the curriculum. Participating women are enthusiastic about the cultural elements embedded in the curriculum such as including traditional foods like blue corn mush and mutton broth in a “first foods” lesson and addressing cradleboards in a “safe sleep” program.

Promising Policies and Looking Ahead

Despite challenges, these programs and a return to Indigenous priorities can lead to improved mental health outcomes. Federal policies can also play a role.

- In 2022, the Biden Administration released guidance on a new federal commitment to incorporate Indigenous Traditional Ecological Knowledge (ITEK) into policy. Stakeholders believe public health and climate change will be logical policies in which to integrate ITEK.

- The Affordable Care Act led to the expansion of Medicaid in most states, disproportionately benefiting American Indian and Alaska Native populations. Tribal leaders are currently working to reenroll Tribal populations who lost coverage amidst recent Medicaid unwinding.

- The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) is working with Tribal leaders to reassess and update the National Tribal Behavioral Health Agenda, which provides historical context, cultural wisdom, and strategic planning to help organizations adopt priorities, encourage collaboration, and evaluate progress in behavioral health outcomes for Tribal populations.

In other policy decisions, the U.S. Supreme Court recently ruled 5-4 that the federal government must repay Tribal healthcare programs that were underfunded, potentially diverting hundreds of millions of healthcare dollars to the Indian Health Service. In response to the ruling, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Secretary Xavier Becerra stated, “We urge Congress to act on the FY 2025 President’s Budget proposal…to protect the overall appropriation for the Indian Health Service and create more adequate and stable funding into the future.”

——————————-

Watch Dr. Warne’s 2024 Weitzman Institute Symposium presentation, “Representation Matters: Indigenous Peoples in the Health Sciences,” on Vimeo.