By: Brandon Azevedo, MPH; Tonantzin Juarez, MS; Angela Taylor, MPH

The recent conversations around women and their healthcare began long before the Supreme Court’s June decision on abortion. Sixty years ago, women began organizing over discrimination against women in healthcare, biomedicine, and research. The Women’s Health Movement (WHM) led to significant policy and cultural changes, including the inclusion of women in clinical trials, the creation of the Congressional Caucus for Women’s Issues, and the establishment of the Office of Research on Women’s Health. This Women’s History Month, we want to highlight the key milestones of the WHM and discuss how it was key to moving us closer to gender equality in the health and biomedical research fields.

Origins of the Movement

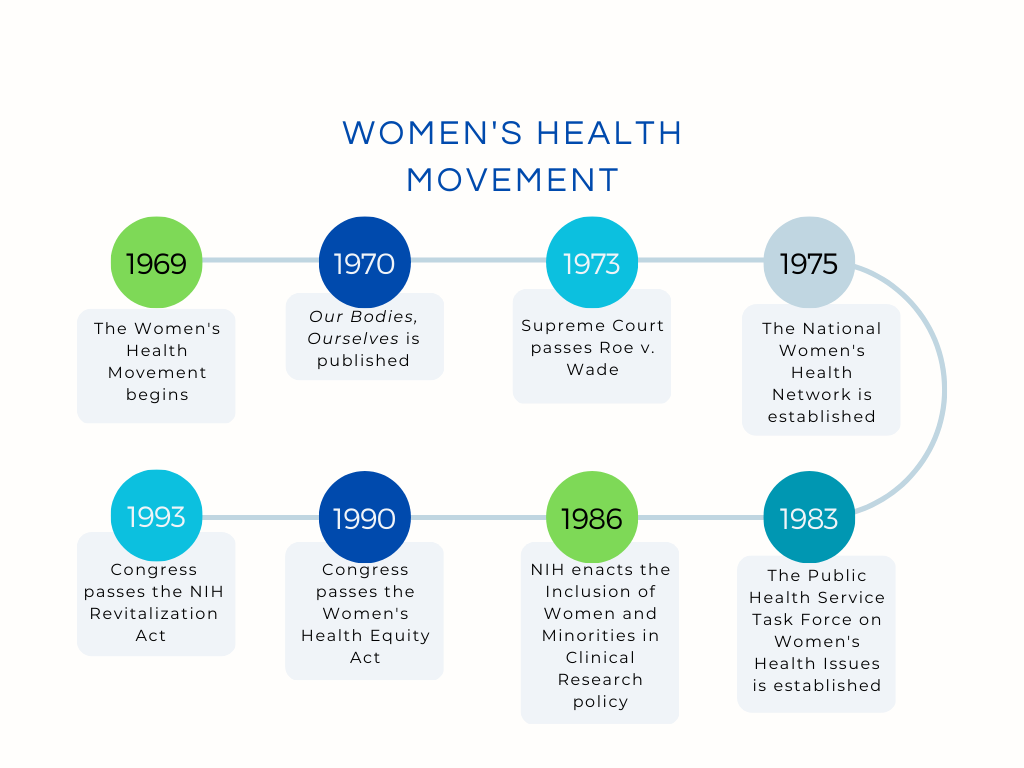

The WHM emerged in the 1960s with the goal of improving healthcare for all women. Specifically, women activists during these two decades focused on awarding women the right to their own reproductive rights. Three significant events that helped propelled this movement including the publication of the book Our Bodies, Ourselves in 1970, the passage of Roe v. Wade in 1973 and the founding of the National Women’s Health Network in 1975, which to this day, continues to be one of the leading women’s health organizations in the United States.

However, even though the movement originally focused on sexual health and abortion, it eventually grew to challenge sexism inherent in the healthcare system. This included challenging traditional doctor-patient relationships and misogyny, and fighting for Title IX of the Higher Education Act Amendments of 1972 and the Public Health Service Act of 1975. The passage of those two key laws lifted restrictions for women in the medical field, and resulted in over 20,000 women graduating from medical school between 1970-1980. This compares to the 14,000 women that graduated between 1930-1970.

Federal Policy Changes

The 1980s and 1990s further propelled the WHM with federal policy changes, particularly regarding including women in clinical research. These changes came after the Food and Drug Administration in 1977, issued a guideline banning a majority of women from clinical research for childbearing reasons. The Congresswomen’s Caucus, now the Congressional Caucus for Women’s Issues, was formed in 1977 and brought women’s issues to the forefront in Washington, D.C, by proposing and supporting legislation that focused on equal pay, women’s health, domestic violence, and maternal health among others.

The 1980s and 1990s further propelled the WHM with federal policy changes, particularly regarding including women in clinical research. These changes came after the Food and Drug Administration in 1977, issued a guideline banning a majority of women from clinical research for childbearing reasons. The Congresswomen’s Caucus, now the Congressional Caucus for Women’s Issues, was formed in 1977 and brought women’s issues to the forefront in Washington, D.C, by proposing and supporting legislation that focused on equal pay, women’s health, domestic violence, and maternal health among others.

Efforts to include women in research and clinical trials began in 1983, when the Public Health Service Task Force on Women’s Health Issues was established. In 1985, this taskforce released a report calling for the inclusion of women in clinical trials and more research that focused on diseases impacting women’s health. Several members of Congress from the Congressional Caucus for Women’s Issues also urged that women be included in clinical trials. This resulted in the National Institutes of Health (NIH) adopting the Inclusion of Women and Minorities in Clinical Research policy to ensure that clinical trials and research were designed to include women and minorities. However, in 1990, the General Accounting Office (GAO) report found that the policy had been applied inconsistently and communicated ineffectively. In response, Congress passed the Women’s Health Equity Act of 1990, which resulted in the establishment of the Office of Research on Women’s Health (ORWH). In 1993, Congress updated the 1986 NIH inclusion policy to ensure that women and minorities be included in all clinical research, and ensure that there were recruitment outreach programs and support for these groups.

More Progress is Needed

The WHM resulted in significant movement towards equality in healthcare, biomedicine, and government, but more needs to be done. A recent study by the Kaiser Family Foundation found that 29% of women reported that their doctor had dismissed their concerns, and 38% of women reported having had at least one negative experience with a healthcare provider, compared to 32% of men. Further, although women make up 75% of the hospital workforce, they only hold roughly 15% of the CEO positions in healthcare organizations. Lastly, women made up 56% of clinical trial participants in 2020, but only 25% of those participants were people of color.

We must commit to uplifting women and include them in conversations around healthcare quality, the workforce, and research. Additional efforts are especially needed to increase racial/ethnic inclusion and representation in those areas. The FDA’s recent draft guidance aimed at enrolling more underrepresented racial and ethnic participants into clinical trials, and the All of Us Research Program are two examples of initiatives striving to do just that, and others should follow their lead. Policymakers must continue striving for equality and inclusion in healthcare and research by supporting initiatives that improve the health and well-being of all people, regardless of sex or race.